This is a historical story about one of, if not the most important watchmaker in history; Abraham Louis Breguet (1747 – 1823). The importance of this man’s creations and his contribution to the art of horology are unparalleled.

In this article we will highlight the breathtaking creations and the important milestones Breguet achieved in his life.

Abraham Louis Breguet was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, to Jonas-Louis Breguet and Suzanne-Marguerite Bolle. His ancestors, contrary to what many people think, were French, not Swiss. Since they were Protestants, they had to flee France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

After his father died in 1758 when Breguet was only ten years old, his mother remarried with Joseph Tattet, who came from a family of watchmakers. This sad and devastating event, the untimely death of Abraham’s father, is in fact the unintentional birth of the world’s greatest watchmaker.

At the age of 15, young Breguet started to show interest in the stepfather’s family business, and began his internship with a still unknown Versailles watchmaker. It didn’t take long before his tutor and other watchmakers started to notice the brilliance of the young student. He strengthened his knowledge by following classes in mathematics and when he finally finished his apprenticeship in 1775, he married Cécile Marie-Louise L’Huillier. That same year, at the age of 28, Breguet established the Breguet Watchmaking Company in Paris. The legendary watch brand was born.

In the years to come, Breguet proved himself to be of unparalleled value to the world of horology with numerous inventions, multiple striking designs and a new way of selling watches to those who showed interest.

Besides his connections to the royal family, Breguet developed friendships and relations with multiple important people over the world. He produced the very first wristwatch for Caroline Murat, the queen of Napels. His first carriage clock for Napoleon Bonaparte, and a four minute tourbillon for the King George III England (all while these two men were fighting against each other in war). And possibly the most important, an astounding timepiece both in aesthetics and complications for Marie-Antoinette (we will go in depth on this particular piece in another article).

Besides his work-related connections with the important people above, Breguet obviously developed multiple friendships with fellow watchmakers around the world. John Arnold, the leading chronometer maker based in England, was so impressed by the creations from Breguet that he asked him to take his son on an apprenticeship. The mutual friendship and feeling of respect between these two watchmakers growed, and in turn, Breguet’s son Antoine-Louis, followed an apprenticeship with John Arnold.

Marie Antoinette

We will highlight the most important creations invented by Breguet. There’s enough information to write an article about every single invention on its own, but since we think this article should be an ‘easy’ read, we will highlight these important inventions in a concise manner.

- 1780 – Breguet creates an Automatic ‘self-winding’ movement, the ‘Perpétuelle’. While Breguet doesn’t hold the title for creating the first ‘automatic’ watch ever produced, his type of escapement was different in many ways to the first example made in 1776 by Abram Louys Perrelet. Breguet’s creation consisted of a pocket watch with an oscillating weight ‘à secousses’ which moved naturally on the movements made by the wearer of the watch. The weight pushed up two barrels bit by bit with every ‘step’, automatically getting locked when the two mainsprings were fully wound.

- 1783 – It is generally known that Breguet was interested in repeating pocket watches, resulting in many different innovative repetition timepieces made by his hands. Breguet invented a new way in creating tones, in comparison to a repeater striking with hammers on a bell. Breguet created gong-springs, with different lengths for creating different tones for the hours and quarters.

- 1790 – To find the forerunner of the modern Incabloc shock protection mechanism, we have to go back to 1790. In this year, Breguet presented the ‘Pare-Chute’ invention. With the idea of making a movement less fragile, Breguet thought of an innovative design to protect the most fragile part of a watch; the pivots of the balance wheel. By giving them a cone-shaped form and holding them in place with small dishes of matching shape, mounted on a strip spring, the pivots received more ‘correction’ space when the watch suffered a blow. From 1792, his “perpétuelle” watches were all equipped with it. Soon all his watches were equipped, and he presented the definitive version at the national exhibition of 1806.

Christiaan Huygens

- 1795 – The original flat balance spring was invented by the Dutch mathematician Huyens back in 1675, but did not entirely satisfy the ever improving Breguet. Breguet applied himself to the ‘problem’ of inventing a balance with an improved isochronism (In horology, a mechanical clock or watch is isochronous if it runs at the same rate regardless of changes in its drive force, so that it keeps correct time as its mainspring unwinds or chain length varies).

In the year 1795 Breguet ‘solved’ it by drawing the outer extremity of the spiral in towards the centre, following a precisely calculated curve. Thus endowed with the ‘Breguet curb’, the balance spring henceforth became concentric in form. Watches gained in precision, and the balance staff wore less quickly. Breguet also perfected a bimetallic compensation bar in order to cancel out the effects of changes in temperature on the balance spring. In today’s watch industry, almost every great watchmaking firm adopted the Breguet balance spring.

- 1796 – This year marks the first sale of the ‘Souscription’ watch made by Breguet. This relatively large watch (61mm) was fitted with one hand and a relatively ‘simple’ yet very special movement. These launched through advertisement brochure watches were sold by Breguet on a subscription basis, hence the name ‘Souscription’. Interested buyers had to make a down payment of 1/4th of the price to place an order. These watches were reliable and affordable; and proved to be a great success, attracting a large new clientele. Some 700 were made, with a choice of either a gold or silver case.

- 1799 – Another relatively ‘simple’ construction yet extremely innovative. Back in the 18th century there was no alternative way to tell the time except for the long existing repeating pocket watches. Breguet changed that with the sale of the first ‘A tact’ watch in 1799. Breguet produced watches with mechanisms that enabled their wearers to tell the time by touch. A pointer, often in the shape of an arrow, on the front lid of the case mirrors the position of the hour hand within the watch. By feeling the position of the pointer, the wearer can deduce the time from its position in relation to little bulges aligned with the hours. Going through books and searching the auctioned ‘A Tact’ pieces by Breguet we find that many have been superbly decorated with enamel, pearls and diamonds. Not necessarily something you expect to find on a ‘watch for the blind’.

Obviously known for his innovation in complications, Breguet is also renowned for his style in hands and numerals. The recognizable open-moon tipped hands (Breguet hands) are comparable with the hands created by Jean Antoine Lepine, born in 1720. Besides the hands, Breguet also refined the Arabic numerals to what are now called ‘Breguet numerals’. It is said that Rolex, of all well known Swiss watch brands, is the only maison that hasn’t officially cataloged a watch with Breguet numerals. An evident example to show how frequent and indispensable Breguet’s work is in the modern world of horology.

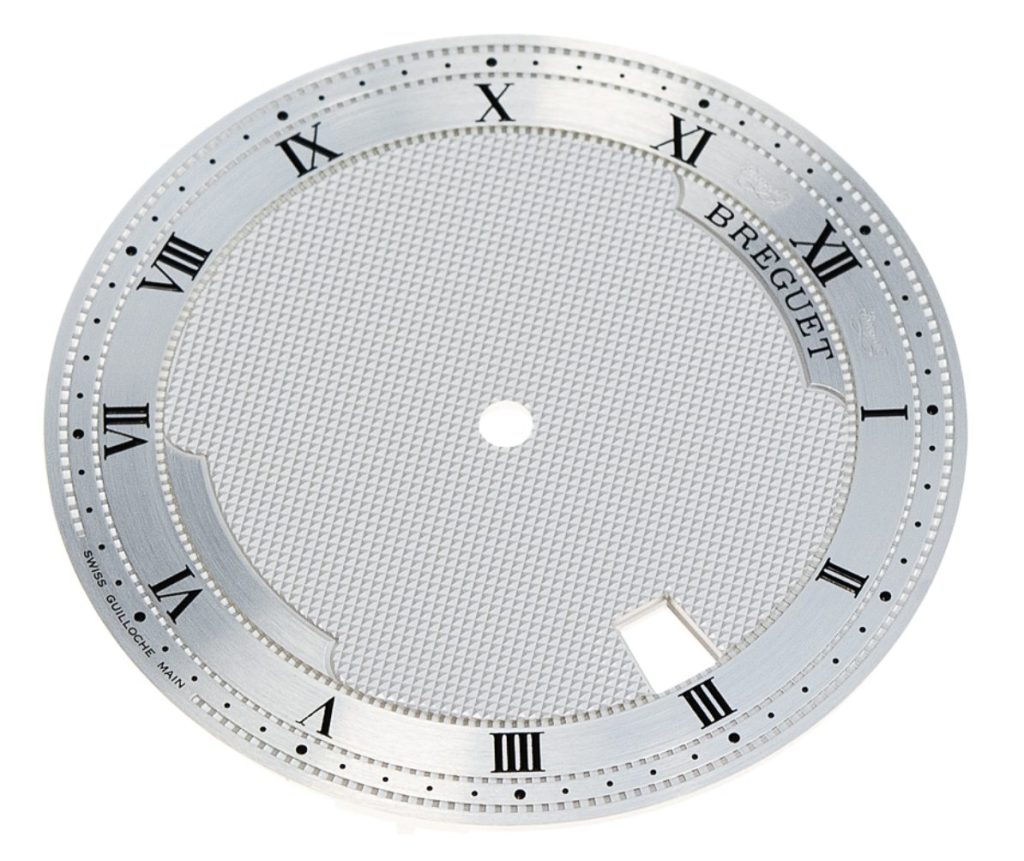

Besides the hands and numerals, Breguet is known for his use of guilloche (engine turning) patterns in dials. Guilloche is a type of craftsmanship that involves the precision-engraving of materials by using engine-turning lathes. By creating grids made in straight, curved or broken lines, the processed material begins to show a repetitive pattern. In comparison to other makers and brands, who used guilloche engravings only by decorating the casing of a watch, Breguet was drawn by not only the aesthetic aspects, but also the functional character of these guilloche dials. The anti-reflective characteristics increased the readability of the dial, and provided a much better surface to counteract scratches and tarnishing.